I spent several hours this weekend reading through the comments section of the NYTimes ‘Tell Us Why It’s Ethical to Eat Meat” contest and getting progressively depressed by the tendency of ‘meat-eaters’ to dismiss vegans as elitist, irrational, extreme or simple wrong and to justify their meat consumption in a variety of predictable arguments–some more absurd than others. See this ‘Defensive Omnivore Bingo‘ for typical responses to veganism and then compare this to the comments section of the contest (they’re all there). I remember making these same arguments when I was an enthusiastic meat-eater not so long ago. It’s funny, when you’ve been vegan for a while, you start to realize you’ve heard all the arguments and all the justifications for eating meat. They are all some variation of one of the same set of reasons. And what’s particularly funny is that most meat-eaters who are making the justifications act like they’re the first to ever make this argument. In the three years I’ve been vegan, I’ve gotten to the point where within a couple of moments I can recognize which justification it is… It’s the “It’s natural” line, or the “What about plants?” line, or the “God put animals on the planet to eat” line, or “It’s tradition” or “I like the way it tastes and I have the right to choose what I eat” or “I only eat ‘humanely slaughtered’ meat”. The list goes on, but ultimately all arguments boil down to one of the set. The downside to this predictability of justifications is that it gets old having to listen to the same tired old justifications (none of which are particularly convincing). The upside to this predictability of justifications is that you’ll have no shortage of practice for responding to these arguments and honing your counter-arguments. You can try out different strategies and see which are most effective in furthering the conversation.

I spent several hours this weekend reading through the comments section of the NYTimes ‘Tell Us Why It’s Ethical to Eat Meat” contest and getting progressively depressed by the tendency of ‘meat-eaters’ to dismiss vegans as elitist, irrational, extreme or simple wrong and to justify their meat consumption in a variety of predictable arguments–some more absurd than others. See this ‘Defensive Omnivore Bingo‘ for typical responses to veganism and then compare this to the comments section of the contest (they’re all there). I remember making these same arguments when I was an enthusiastic meat-eater not so long ago. It’s funny, when you’ve been vegan for a while, you start to realize you’ve heard all the arguments and all the justifications for eating meat. They are all some variation of one of the same set of reasons. And what’s particularly funny is that most meat-eaters who are making the justifications act like they’re the first to ever make this argument. In the three years I’ve been vegan, I’ve gotten to the point where within a couple of moments I can recognize which justification it is… It’s the “It’s natural” line, or the “What about plants?” line, or the “God put animals on the planet to eat” line, or “It’s tradition” or “I like the way it tastes and I have the right to choose what I eat” or “I only eat ‘humanely slaughtered’ meat”. The list goes on, but ultimately all arguments boil down to one of the set. The downside to this predictability of justifications is that it gets old having to listen to the same tired old justifications (none of which are particularly convincing). The upside to this predictability of justifications is that you’ll have no shortage of practice for responding to these arguments and honing your counter-arguments. You can try out different strategies and see which are most effective in furthering the conversation.

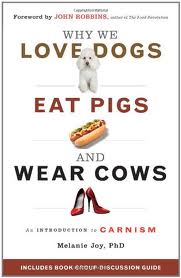

As I was struggling with my own reactions to reading the hundreds of comments justifying meat consumption (none of which actually addressed the issue of ethics), I found myself thinking about ‘carnism’. During my Animals, Ethics and Food class this past quarter, I had us read a couple of chapters from Melanie Joy’s Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs and Wear Cows. The most poignant contribution of this book, in my opinion, is the introduction of the term ‘carnism’ or ‘carnist’ to describe someone who chooses to eat meat. Joy (pp 29-30) explains carnism in the following way:

“If a vegetarian is someone who believes that it’s unethical to eat meat, what, then, do we call a person who believes that it’s ethical to eat meat? If a vegetarian is a person who chooses not to eat meat, what is a person who chooses to eat meat?

Currently, we use the term ‘meat eater’ to describe anyone who is not vegetarian. But how accurate is this? As we established, a vegetarian is not simply a ‘plant eater’. Eating plants is a behavior that stems from a belief system. ‘Vegetarian’ accurately reflects that a core belief system is at work: the suffix ‘arian’ denotes a person who advocates, supports or practices a doctrine or set of principles.

In contrast, the term ‘meat eater’ isolates the practice of consuming meat, as though it were divorced from a person’s beliefs and values. It implies that the person who eats meat is acting outside of a belief system. But is eating meat truly a behavior that exists independent of a belief system?

In much of the industrialized world, we eat meat not because we have to; we eat meat because we choose to. We don’t need meat to survive or even be healthy…We eat animals simply because it’s what we’ve always done, and because we like the way they taste. Most of us eat animals because it’s just the way things are.

We don’t see meat eating as we do vegetarianism–as a choice, based on a set of assumptions about animals, our world, and ourselves. Rather, we see it as a given, the ‘natural’ thing to do, the way things have always been and the way things will always be. We eat animals without thinking about what we are doing and why because the belief system that underlies this behavior is invisible. This invisible belief system is what I call carnism…

Carnism is the belief system in which eating certain animals is considered ethical and appropriate. Carnists–people who eat meat–are not the same as carnivores. Carnivores are animals that are dependent on meat to survive. Carnists are not merely omnivores. An omnivore is an animal–human or nonhuman–that has the physiological ability to ingest both plants and meat. But, like ‘carnivore,’ ‘omnivore’ is a term that describes one’s biological constitution, not one’s philosophical choice. Carnists eat meat not because they need to, but because they choose to, and choices always stem from beliefs.”

I’ve read a few critiques of NYTimes contest by the vegan community and I have been thinking about the contest and its value (or not) over the past few days. It seems to me this contest may be an opportunity to reflect on carnism as the status quo in the sense that it’s asking people to come up with ethical defenses for what has, for so long, just been viewed as the way things are. We so infrequently challenge what we take to be fundamental norms. But I think there is great power in making an effort to make invisible belief systems visible because when we make them visible, we may see things about them that we didn’t see before. For instance, in trying to come up with ethical defenses for carnism, it may become clear that the justifications are driven more by taste, evolution, tradition, habit, or culture than by ethics. What other practices have been justified by taste, evolution, tradition, habit or culture and how have these denied or ignored ethical considerations?

I’ll be interested to see what comes of this contest. Admittedly, my expectations are pretty low for this to spark a more nuanced discussion about carnism, the status quo, and identifying and challenging invisible belief systems since Michael Pollan is one of the judges. (No matter how vehemently he defends his own meat consumption as ‘ethical’, I remain wholly unconvinced.) I expect it will be the same arguments about getting back to ‘humanely raised and slaughtered meat’, about organic, local, free-range, cage-free. etc., about eating less meat, the same dismissiveness about the extremism of vegetarian/vegan lifestyles–all as a way to skirt the more fundamental issue of eating animals in the first place. But here’s to hoping. And, at least, here’s to hoping that reading the ethical defenses of meat eating might spark some people to rethink their own belief systems as embedded in carnism.

Follow

Follow

I sometimes wonder who it is that donates to sanctuaries and other safe animal spaces, and if they eat meat. And i can’t help but think that it might all not be wrapped up in an individualized system of consumptive guilt – buying off bad behavior (not unlike carbon offsets for flights) – recognizing, of course, that not all people who donate to sanctuaries or other animal-first programs are meat eaters, but also being self-consciously aware that there are strong contradictions in many of us. For instance, who donates to save endangered species? Who donates to La Montagne des Singes? And which of them buy leather shoes, belts, purses?

I mostly am curious about the inability (or unwillingness?) of people to address actual “ethics” outside of their personal consumptive habits. “I know it is wrong, but i still..”, or conversely, “I don’t think it’s wrong and the ethical framing for my choice is situated in …” Unfortunately, Wendy Brown comes in handy here, in the “morality” of liberal economics where homo economicus becomes morally unquestionable in all his/her actions, where “all dimensions of human life are cast in terms of a market rationality…[that] does not simply assume that all aspects of social, cultural, and political life can be reduced to a calculus; rather, it develops institutional practices and rewards for enacting that vision…through discourse and policy promulgating its criteria, neoliberalism produces rational actors and imposes a market rationale for decision making in all spheres…In making the individual fully responsible for her- or himself, neoliberalism equates moral responsibility with rational action; it erases the discrepancy between economic and moral behavior by configuring morality entirely as a matter of rational deliberation about costs, benefits, and

consequences” (2005: 40-42). What comes to question, then, is what is ethics? And when did it become so watered down to simply mean personal consumption preferences?

Tish, Thanks for the response! I imagine it’s a wide mix of people donating to sanctuaries. For instance, with Pigs Peace, I think there are quite a few people who donate because of a deep commitment to animal rights, whereas others may donate because they have an affinity for pot-bellied pigs and still eat bacon. Also, I imagine it really depends on the type of animals at the sanctuary. For instance, I was talking to someone a couple of months ago who volunteers at a horse sanctuary every week. In the next sentence, she was telling me that she wasn’t one of those ‘animal rights’ people (though, she made a point to tell me she doesn’t eat veal). It’s odd to reflect on where we all choose to draw our lines and how we rationalize our choices to draw the lines where we do. And you’re right–we always live with contradictions in our behavior and belief systems.

I’ve been trying to understand for myself ‘what is ethics’ recently–especially since seeing the announcement for this contest. My response to the comments on the contest justifying meat consumption was that these are not ethical justifications. Or are they? It seems to me that ethics are often boiled down to our consumptive choices because it’s our most comfortable entry point for enacting our moral belief systems. And it’s a public way of announcing our belief systems to others in a highly capitalized system. The whole ‘vote with your dollar’ mumbo jumbo. But of course there are plenty of folks (e.g., Bob Torres) who argue that we cannot buy our way to more ethical living. And I would certainly agree with this. If we settle into thinking we can lively ethically by simply buying the right things, I think we risk settling into complacency within a system that is deeply flawed in the first place. That being said, I think veganism as a lifestyle choice is a powerful statement about an ethical commitment to nonviolence, but not just any veganism, right? There are ‘ethical’ vegans who focus so much on just consuming products that don’t harm animals that they forget about the exploitative labor practices or the environmental destruction involved in the production of that good, for instance. True veganism (as I think Torres gets at) takes into account all of the intersections of oppression involved in a capitalist economic system. He advocates working for an alternative to capitalism–pushing a Marxist social anarchist alternative vision of society that is kinder, more compassionate, and fundamentally less oppressive. True ethical veganism, then, becomes not just an anti-speciesist project about eliminating animal exploitation, but an expansive social justice project that is anti-racist, anti-sexist, etc. And while one enactment of this is to try to change our consumptive habits to reflect this ethic, we also need to think more broadly–to question the system that creates this exploitation of humans, animals and the environment in the first place and to recognize our implicatedness in it.

And, I’ve really got to read some Wendy Brown. 🙂